Shackleton’s Endurance - The Survival That Became Legend

The ship’s timbers screamed as Antarctic ice closed like a living thing around the Endurance.

Ernest Shackleton stood on deck on October 27, 1915, watching his vessel crumble beneath the inexorable pressure of the Weddell Sea ice pack. The sounds that emerged from the dying ship haunted the men for months afterward—groans like a creature in agony, sharp cracks like breaking bones, the deep bass rumble of timbers being crushed to splinters.

The crew would later describe the sounds—twenty-eight men stood on the ice watching their home, their equipment, and their expedition’s original purpose reduced to wreckage.

Twelve hundred miles from the nearest civilization. No radio. No possibility of rescue. The Antarctic winter closing in around them like a noose.

What happened next would transform into one of history’s most legendary survival stories—a tale that balances documented fact with elements of legend. For twenty-two months, twenty-eight men survived conditions that had killed countless previous explorers.

They lived on drifting ice that shrank daily beneath their feet. They crossed eight hundred miles of the world’s most violent ocean in boats barely large enough to hold them. And in their darkest hour, crossing uncharted mountains in a final desperate bid for rescue, some of them felt the presence of something—or someone—that shouldn’t have been there at all.

The Endurance expedition became legend not just because they survived, but because their survival seemed to require something beyond human endurance. Something that straddled the space between natural and supernatural, between what we can measure and what we can only experience.

The Crushing: When the Ice Came Alive

The Endurance didn’t sink like most ships—didn’t go down in a storm or strike a reef or burn from accident. Instead, it died slowly, crushed by forces so vast that human resistance meant nothing.

The Weddell Sea ice pack, thousands of miles of frozen ocean, had trapped the ship in January 1915, and through the months that followed, the ice demonstrated its terrible patience.

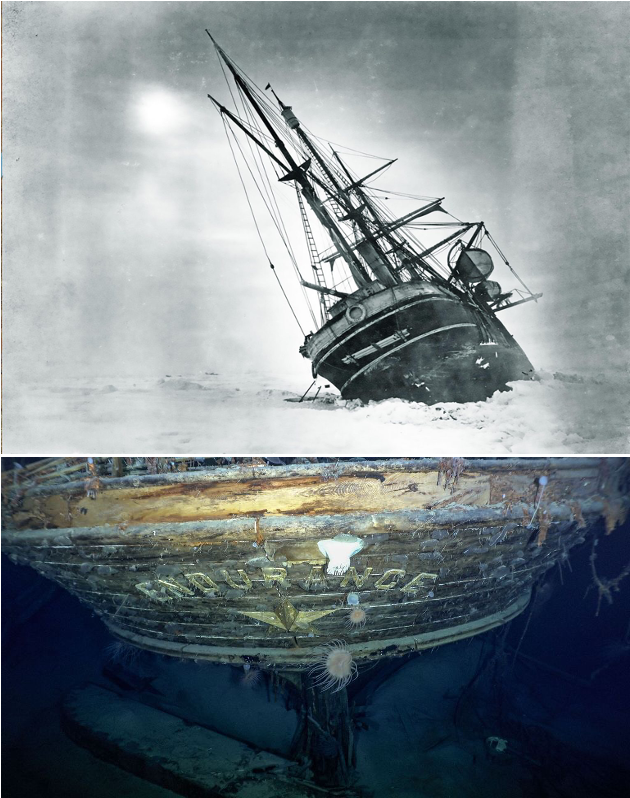

Photographer Frank Hurley captured images that still haunt maritime history: the Endurance tilted at impossible angles, its stern lifted clear of the ice by pressure that bent steel plates like paper, its rigging a web of frozen lines against the Antarctic sky.

Thomas Orde-Lees, the expedition’s motor expert, wrote in his diary:

“The noise is indescribable. One has to experience it to understand—it is the death of a ship, and it sounds like the end of the world.”

The men salvaged what they could before the final collapse—food, clothing, the three lifeboats that would become their salvation. But they had to leave behind most of their equipment, their scientific instruments, Hurley’s glass plate negatives documenting their journey. Shackleton himself is said to have destroyed his journal, choosing survival over historical records.

When the Endurance finally went under on November 21, 1915, slipping beneath the ice that had trapped it, the men stood in silence watching their last connection to civilization disappear.

They were now castaways on moving ice, hundreds of miles from land, with no way to communicate their position and no hope of rescue until the Antarctic summer—months away—might open water routes for ships that didn’t know they needed rescuing.

Patience Camp: The Slow Horror of Waiting

What the men called “Patience Camp” tested them in ways more psychologically devastating than the ship’s destruction.

At least the crushing of the Endurance had been dramatic—terrible but finite. Now they faced something worse: the slow realization that they were drifting on ice that moved according to currents and winds beyond their control, that was visibly shrinking as temperatures rose, that could split beneath their feet at any moment without warning.

Shackleton established camp routines with almost obsessive precision. Daily duties, meal preparations, equipment maintenance, entertainment schedules.

Looking back, historians recognize this as sophisticated crisis psychology—creating islands of normalcy within chaos, giving each man purpose that prevented the drift toward helplessness.

But the men themselves experienced it as a strange theatrical performance, maintaining civilized routines while living on slowly melting ice above an ocean that would kill them in minutes if they slipped in it.

The Antarctic summer brought not salvation but new terrors.

The ice began breaking up faster, creating open leads of pitch black water between floes. One night they woke to find their camp split in two, men shouting across a widening gap, scrambling to reunite the group before the floes drifted too far apart. They moved camp repeatedly, each time leaving behind more equipment, a constant calculation of what was essential for survival versus what they could no longer afford to carry.

Orde-Lees documented the psychological toll in his diaries: men becoming withdrawn, small conflicts magnifying into serious tensions, the constant gnawing awareness that their ice home was disappearing beneath them.

“We are on a piece of ice perhaps a half-mile across, drifting God knows where,” he wrote. “The unreality of it is maddening. We maintain routines as if we were in a proper camp, yet any moment the ice beneath our tents might split and drop us into the sea.”

The isolation pressed on them incessantly. In the days before radio, castaways could vanish without trace, their fates unknown until years later when searchers might—or might not—find evidence of their end.

The Endurance crew knew they were invisible, that the world had no idea where they were or whether they still lived. That knowledge created a particular kind of despair that Shackleton fought against daily, over and over again, to prevent it from spreading through his men.

The Boat Journey: Crossing the Drake Passage in Lifeboats

When the ice finally released them in April 1916, five months after the ship’s sinking, it dropped them into a nightmare that made ice camp seem almost comfortable.

Three lifeboats—the James Caird, Dudley Docker, and Stancomb Wills—barely large enough for twenty-eight men and their remaining supplies.

Eight hundred miles of open ocean to the nearest land, Elephant Island. And between them and that rocky shore: the Drake Passage, the most violent stretch of water on Earth where Atlantic and Pacific oceans meet in perpetual storm.

Worsley’s navigation during those sixteen days represents seamanship of almost supernatural precision. Using a sextant on boats that pitched through waves tall as houses, taking sightings between clouds that obscured the sky for days at a time, he somehow kept them on course.

His journal entries reveal the impossible conditions:

“Taking sights was like trying to measure the altitude of a star from the saddle of a bucking horse. The boat would soar up a wave face, hang suspended for a moment, then plunge into the trough. Had to wait for that suspended moment and hope for clear sky.”

The men themselves became something less than human during that crossing. Soaked constantly in near-freezing water, unable to sleep except in brief exhausted moments, they existed in a state that survivor accounts struggle to describe.

Lionel Greenstreet, first officer of the Endurance, wrote later:

“After the first few days, time stopped meaning anything. We were just bodies that moved when told to move, that bailed water when the boat filled, that existed in a kind of waking dream where cold and wet and exhaustion merged into a single endless state.”

When they finally reached Elephant Island on April 15, 1916, some men had to be lifted from the boats—their legs wouldn’t hold them after sixteen days of constant motion and cold.

They had survived though, a passage through waters that routinely killed experienced sailors in proper ships.

But Elephant Island, while land, again offered no salvation.

Just a rocky shore in one of the most remote, inhospitable places on Earth. No food beyond what seals and penguins they could kill. No shelter beyond their overturned boats. No hope of rescue—shipping lanes came nowhere near this desolate place.

Shackleton understood immediately what his men perhaps refused to accept: they had merely traded one death sentence for another, slightly less immediate. Elephant Island would kill them eventually, just more slowly than the ocean would have.

The Fourth Man

The choice Shackleton made next has become the stuff of maritime legend: take one of the lifeboats, the James Caird, and attempt an eight-hundred-mile journey across the world’s worst ocean to South Georgia, where whaling stations offered the only realistic chance of mounting a rescue operation.

And if they reached South Georgia’s south shore—the only side approachable from their direction—they would need to cross the island’s uncharted mountain interior to reach the whaling stations on the north coast.

No one had ever crossed South Georgia’s interior.

The mountains were mapped as blank spaces on charts, marked only with elevations that suggested peaks high as the Alps but compressed into a much smaller space, creating terrain of impossible steepness.

But Shackleton, along with Worsley and Second Officer Tom Crean, set out to do just that, leaving the majority of the expedition on Elephant Island under Frank Wild’s command, praying they could bring rescue before starvation or scurvy claimed their companions.

The James Caird voyage itself deserves its own legend—twenty-two feet of modified lifeboat crossing eight hundred miles of Antarctic ocean.

Worsley’s navigation through storms that nearly capsized them hourly. The ice that built up on the boat until they had to climb onto the hull with axes to chip it off or risk capsizing from top-heaviness. The waves that came over them so constantly that everything—men, supplies, sleeping bags—remained perpetually soaked in freezing water.

They reached South Georgia on May 10, 1916, landing, as expected, on the uninhabited southern shore, fifty miles of mountain terrain away from help. Exhausted, malnourished, their equipment reduced to almost nothing, the three men began what should have been an impossible crossing.

What happened during those thirty-six hours of continuous climbing has never been fully explained.

Shackleton himself first mentioned it publicly in his 1919 book South: The Endurance Expedition:

“When I look back at those days I have no doubt that Providence guided us, not only across those snowfields, but across the storm-white sea that separated Elephant Island from our landing-place on South Georgia. I know that during that long and racking march of thirty-six hours over the unnamed mountains and glaciers of South Georgia it seemed to me often that we were four, not three.”

Worsley, in his own account Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure (1931), confirmed the experience:

“Shackleton privately told me that he had the strange feeling that there was another person with us... I did too.”

Crean, characteristically laconic, simply said when asked about it years later:

“There was something with us. I felt it.”

Three men. But the persistent, unshakeable sense that a fourth presence accompanied them across those mountains. Not imagined. Not hallucinated. Experienced. A presence that seemed to guide them when navigation became impossible, to encourage them when exhaustion threatened to stop them, to protect them when one misstep would have meant death.

T.S. Eliot captured this phenomenon in The Waste Land (1922), writing:

“Who is the third who walks always beside you? / When I count, there are only you and I together / But when I look ahead up the white road / There is always another one walking beside you.”

Modern research has documented what psychologists call the “Third Man Factor”—a phenomenon where individuals in extreme survival situations report sensing an invisible presence that provides guidance or comfort.

John Geiger’s comprehensive study The Third Man Factor (2009) documents dozens of cases across different environments and cultures: mountaineers, shipwreck survivors, solo sailors, even victims of traumatic accidents reporting this same presence.

Neurologist Dr. Peter Suedfeld suggests the brain, under extreme stress and exhaustion, may generate this sense of presence as a coping mechanism. Dr. Ben Alderson-Day’s research shows that up to 80% of people in prolonged isolation or extreme conditions experience “phantom social presence”—the persistent feeling of companionship when demonstrably alone.

But the scientific explanations, while valid, don’t diminish the experiential reality of what Shackleton, Worsley, and Crean felt on South Georgia. Something—whether generated by their exhausted minds or existing independently of them—accompanied them across terrain that should have killed them.

And that something led them, after thirty-six hours without rest, directly to the Stromness whaling station.

When they stumbled into the station on May 20, 1916, the whalers didn’t recognize them at first. These weren’t men—they were scarecrows, walking skeletons with matted hair and beards, their clothes in tatters, their faces blackened by frostbite and weather. The station manager asked who they were. Shackleton replied simply: “My name is Shackleton.”

The whistle that called the whalers to work each morning—Shackleton heard it during their final approach to Stromness—meant more than just rescue.

It meant he could now fulfill the promise he’d made: bring every man home alive.

Twenty-Eight Men, Twenty-Two Months, No Deaths

August 30, 1916.

The Chilean tug Yelcho approached Elephant Island through clearing weather. On the rocky shore, twenty-two men stood watching, barely daring to hope.

They had waited four months and eleven days since Shackleton departed. Some had given up hope entirely. Some had convinced themselves he was dead, that they were abandoned. But Frank Wild had maintained discipline, kept them organized, made them believe rescue would come.

And here it came.

Every man accounted for. Every man alive. After 634 days since the Endurance was crushed, after months on drifting ice, after the perilous boat journey through the Drake Passage, after waiting on Elephant Island while Shackleton attempted the impossible, not one death. Not from cold, hunger, sickness, accident, or despair.

Comparing this with other expeditions makes this achievement even more remarkable.

Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic expedition lost all five members of the polar party in 1912. Greely’s Arctic expedition lost nineteen of twenty-five men. Franklin’s expedition lost all 129 men. Antarctic and Arctic exploration was measured in deaths—the accepted cost of pushing into those frozen extremes.

Shackleton brought everybody home.

Historians and leadership scholars have spent decades analyzing how this happened. The daily routines that prevented psychological collapse. The careful attention to each man’s mental state. The balance of authority and flexibility. The creation of purpose and meaning when original goals became impossible. All true. All important.

But the men themselves, in their later accounts, attributed survival to something less definable. A collective determination that arose not from individual will but from group cohesion. A sense that they were responsible not just for themselves but for each other.

And yes, sometimes, the feeling that they were being helped by something they couldn’t see or name.

Why the Legend Endures: The Impossible Made Real

The Endurance expedition occupies a unique space in maritime history.

Unlike mystery ships like the Mary Celeste where we’ll never know what happened, every detail of the Endurance survival is documented. We have diaries, photographs and, later, interviews. We know what they ate, where they camped, how they navigated. The expedition is transparent in ways few others are.

Yet documentation doesn’t diminish the impossible nature of what occurred. Knowing how they survived doesn’t make their survival less miraculous. If anything, the more detail we have, the more impossible it seems that they succeeded.

Contemporary adventure literature has elevated Shackleton to mythic status—the leader who brought everyone home, who transformed failure into survival, who refused to accept loss.

Business schools teach the expedition as the ultimate case study in crisis leadership. Military academies analyze his decision-making. Organizations from corporations to governments study his methods for maintaining morale under impossible pressure.

But perhaps the expedition’s deepest legacy lies in what it reveals about human capacity for endurance when survival becomes a collective responsibility.

In an age of individualism, the Endurance story (and never was a ship’s name so apt) reminds us that our greatest achievements often come not from personal heroism but from mutual support, from binding ourselves to others in ways that make abandonment unthinkable.

The Fourth Man phenomenon adds another dimension to this legacy. Whether that presence on South Georgia was a neurological artifact or something more mysterious, it speaks to a truth about extreme experience: at the boundaries of human endurance, the line between material and immaterial, between natural and supernatural, becomes permeable.

The men on that mountain trek existed in a space where normal rules suspended, where the impossible became temporarily possible because it had to be.

Frank Worsley perhaps captured it best in his account:

“We had suffered, starved and triumphed, groveled yet grasped at glory, grown bigger in the bigness of the whole.

We had seen God in His splendors, heard the text that Nature renders.”

The Return: What Survives Legend

The men who returned from the Endurance expedition carried their experience for the rest of their lives.

Some, like Worsley, returned to the sea, eventually commanding ships in World War I. Others, like Orde-Lees, spent decades processing what they’d endured through writing and speaking. Crean retired to a pub in Ireland, where he rarely spoke of his Antarctic experiences but remained friends with those who shared them.

Shackleton himself never fully recovered from the psychological and physical toll of those twenty-two months. He died of a heart attack in 1922, at age forty-seven, while attempting another Antarctic expedition.

His wife requested he be buried on South Georgia—the island he crossed in those thirty-six impossible hours. His grave there, at the Grytviken cemetery, has become a pilgrimage site for sailors and adventurers.

The Endurance itself remained lost, but not forgotten, beneath the Weddell Sea ice for 107 years.

On March 5, 2022, the Endurance22 Expedition located the wreck at a depth of 10,000 feet, remarkably preserved in the cold Antarctic water.

The ship’s wheel still intact. The name clearly visible on the stern. Even the ship’s boot, where Shackleton stood watching the ice close in, looks as if someone might return to it at any moment.

Finding the wreck transformed the Endurance from historical record into tangible artifact.

Today the ship exists simultaneously in three states: as historical fact documented in accounts and photographs, as legendary story of impossible survival, and as physical object resting on the ocean floor. Past, myth, and present material—all occupying the same story.

In our own time, as we face different but equally daunting challenges, the Endurance offers us something more valuable than mere inspiration. It provides evidence that humans are capable of extraordinary feats when we bind ourselves together in mutual responsibility.

That leadership means absolute commitment to those who depend on you.

That survival sometimes requires pushing beyond what seems possible into territory where natural and supernatural, material and spiritual, individual and collective merge.

And perhaps most mysteriously, that even at the absolute limit of human capability—we are not alone.

GO DEEPER:

In our own lives, when we face circumstances that test our endurance—whether personal crisis, professional challenge, or collective hardship—what makes the difference between communities that hold together and those that fragment?

Have you ever experienced a moment when the line between possible and impossible seemed to blur, when survival required something beyond normal human capacity?These prompts are meant for self-reflection and journaling, but I invite you to share your thoughts in the comments.

Previous“Beyond the Cape of Fear: Breaking Through the Darkness of the Unknown” – examining how Portuguese captain Gil Eanes overcame psychological barriers to open the Age of Exploration.

Next in this series: "Sea Dragons Across Cultures: Maritime Dragon Myths Worldwide" – diving into the ancient serpents and wyrms that have haunted seafaring imaginations from Norse fjords to Chinese harbors

About the Author:

Morgan A. Drake crafts dark maritime fantasy that explores the boundaries between historical seafaring traditions and the supernatural. Drawing on years of research into maritime mysteries and folklore, Morgan creates worlds where the line between natural and otherworldly perils blurs with the horizon.

You can find Morgan's fiction at:

References and Further Reading

Primary Historical Sources

Shackleton, Ernest. South: The Endurance Expedition. New York: Macmillan, 1919. Available via Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/southenduranceex0000shac

Worsley, Frank. Endurance: An Epic of Polar Adventure. London: Philip Allan, 1931. Available via Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/enduranceepicofp00wors

Orde-Lees, Thomas. Antarctic Diaries: The Unsung Hero of the Endurance Voyage. Edited by Christine Alexander. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2014.

Hurley, Frank. South with Endurance: Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition 1914-1917. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001.

Modern Historical Analysis

Lansing, Alfred. Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1959.

Alexander, Caroline. The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition. New York: Knopf, 1998.

Huntford, Roland. Shackleton. New York: Atheneum, 1986.

Fiennes, Ranulph. Shackleton. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2021.

The Third Man Factor and Extreme Psychology

Geiger, John. The Third Man Factor: Surviving the Impossible. New York: Weinstein Books, 2009.

Suedfeld, Peter and G. Daniel Steel. “The Environmental Psychology of Capsule Habitats.” Annual Review of Psychology 51 (2000): 227-253.

Alderson-Day, Ben. “Inner Speech: Development, Cognitive Functions, Phenomenology, and Neurobiology.” Consciousness and Cognition 35 (2015): 132-143.

Blom, Jan Dirk. A Dictionary of Hallucinations. New York: Springer, 2010.

Antarctic Exploration Context

Roberts, David. Alone on the Ice: The Greatest Survival Story in the History of Exploration. New York: W.W. Norton, 2013.

Preston, Diana. A First Rate Tragedy: Robert Falcon Scott and the Race to the South Pole. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Further Reading

Gonzales, Laurence. Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why. New York: W.W. Norton, 2003.

Solnit, Rebecca. A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster. New York: Viking, 2009.

A note on the Images: Unless credited, illustrations accompanying the posts are creative interpretations designed to evoke the atmosphere of maritime legend rather than serve as historical documentation. For historical visual references, please consult the sources listed in the references section.