Portal Fantasy: The Psychology of Crossing Between Worlds

The crew of Gil Eanes’s caravel huddled near the mast as Cape Bojador loomed ahead through the Atlantic mist. For fourteen previous expeditions, this had been the turning point—the place where even the bravest captains read the signs of approaching doom and chose retreat over the unknown.

Medieval sailors didn’t simply fear rough waters or treacherous currents at Bojador. They believed they approached a threshold where reality itself changed: beyond this cape, the sun would blacken their skin, the ocean would boil their ships, and sea monsters would rise from depths that marked the edge of the navigable world.

Cape Bojador functioned as a portal in the truest sense—not because it led to another world, but because sailors believed that crossing it meant entering a realm where the fundamental laws of nature no longer applied.

The cape divided existence into two distinct realities: the known world behind them, governed by familiar rules, and the impossible world ahead, where survival itself became uncertain.

When Eanes finally pushed through in 1434, he discovered waters that didn’t boil, a sun that burned no hotter, and no monsters emerging from the depths. Yet his crossing remained a genuine portal moment.

Once he knew what lay beyond Bojador, he could never unknow it. The medieval cosmology that had constrained European navigation for centuries collapsed in the wake of his vessel.

The Age of Exploration began not because the physical world changed, but because human consciousness crossed a threshold it couldn’t recross.

For centuries before and after Eanes sailed past Cape Bojador, humans have been drawn to stories of doorways between worlds—wardrobes leading to Narnia, rabbit holes to Wonderland, storm-tossed ships to enchanted islands, mirrors reflecting impossible rooms.

What separates then a simple boundary from a true portal? And why do we return to this narrative pattern across every culture and era, finding in threshold crossings something that speaks to the deepest structures of human psychology?

Quick note: If you’re reading this in your email, Substack will cut this essay off before the end (it’s a long one). To read the full piece without interruption, click here to read on the website.

The Universal Portal: Thresholds Across Cultures

Portal narratives emerge in every storytelling tradition with remarkable consistency. The specific mechanisms vary—doors, mirrors, storms, mists, whirlpools—but the fundamental pattern persists: a character crosses from familiar territory into a realm where normal rules no longer apply.

Japanese folklore features the hidden door to Ryūgū-jō, the Dragon Palace beneath the sea, where the fisherman Urashima Tarō spends what feels like days in a underwater kingdom, only to return and discover centuries have passed.

Celtic tradition offers fairy rings and hollow hills that lead to the Otherworld, and the sea journey to Tír na nÓg, the Land of Youth, where time flows differently and mortals become immortal.

Greek mythology sends Odysseus on a sea voyage through waters where enchantresses transform men to cattle, the dead walk and speak, and islands appear and vanish like dreams.

Indigenous American traditions describe sacred caves and underwater passages to spirit realms.

Medieval European tales feature enchanted forests where travelers lose their way and emerge into kingdoms that exist alongside but separate from the mundane world.

African and Caribbean maritime traditions tell of passages beneath the waves to the domains of Mami Wata and Yemoja, where water spirits rule according to their own logic.

Despite vast cultural differences, these portal narratives share common structural elements.

First, a physical threshold marker: the wardrobe’s back panel, the rabbit hole’s descent, the fog bank that obscures familiar shores, the whirlpool’s center, the storm that carries ships beyond known waters.

Second, rules change demonstrably on the other side—time flows at different rates, magic functions, physical laws bend or break, moral frameworks shift. Third, the crossing is initially one-way; you cannot simply step back through at will.

Fourth, the protagonist emerges changed by passage, carrying knowledge or scars from the other side that make return to ordinary life complicated, sometimes impossible.

The maritime portal tradition proves particularly rich and persistent.

Water itself functions as a liminal substance—neither solid nor gas, constantly changing form, capable of supporting life while simultaneously threatening it. The horizon line itself creates the ultimate visual threshold, that edge where sky meets sea and vision fails, suggesting infinite possibility beyond sight’s limit.

Fog transforms familiar waters into alien territory within moments, obscuring landmarks and rendering navigation uncertain.

Storms suspend normal rules entirely, reducing experienced sailors to passengers at the mercy of forces beyond human control or comprehension.

Homer’s Odyssey establishes the template for maritime portal narratives. Odysseus’s journey home becoming a voyage through a series of threshold spaces, each operating under distinct rules.

Aeolus’s intervention gifting all winds in a leather bag—nature itself controlled and contained. Circe’s powers transforming men into swine, collapsing the boundary between human and animal.

The passage to the Underworld erasing the ultimate boundary between life and death.

Calypso’s island existing outside the normal flow of time, offering immortality at the cost of remaining forever stuck.

Each crossing tests Odysseus, teaching him something essential while changing him irrevocably.

The Celtic immrama—voyage tales—develop this maritime portal tradition further.

The Voyage of St. Brendan describes islands that shouldn’t exist: a floating crystal column, an island that’s actually a whale, a sea smooth as glass. The Voyage of Bran tells of warriors who sail west and find an island where time moves so differently that stepping back onto Irish soil turns them instantly to dust. The Voyage of Mael Duin becomes a penance journey through increasingly strange waters, each island presenting new laws and new tests.

These stories persist because they capture something true about water’s psychological function. Unlike land with its fixed geography and stable landmarks, the sea remains fundamentally unknowable.

We still discover new species in ocean depths, still find our instruments inadequate to map the complexity beneath the surface.

Maritime portals feel possible in ways that enchanted wardrobes don’t, because the ocean retains its liminal quality even in our scientific age.

Threshold Psychology: Why Portals Captivate Us

Portal narratives resonate because they externalize psychological thresholds we all navigate.

Anthropologist Victor Turner identified liminality as a crucial phase in ritual and social transition—the in-between state where old structures have dissolved but new ones haven’t yet solidified.

Portal crossings dramatize this experience, giving it physical form and narrative structure.

Coming of age functions as portal crossing. The child who enters adolescence doesn’t simply grow taller; they cross into a realm where different rules apply, different responsibilities weigh, different possibilities open and close.

Grief marks another threshold. The person who loses someone central to their existence doesn’t remain in the same world; they cross into a landscape where familiar comforts fail and normal reassurances ring hollow.

Cultural migration forces portal crossing—leaving homeland for foreign territory where language, customs, and social frameworks operate according to unfamiliar logic.

Each of these transitions involves entering territory where, to survive and thrive, you must learn new patterns, develop new skills, and accept that you cannot simply return to who you were before.

The portal fantasy externalizes this internal experience, making visible the invisible boundaries we cross.

Research on narrative psychology suggests portal stories satisfy specific psychological needs.

To begin with, they express desire for transformation while managing fear of change.

We long to become someone new, to escape limiting circumstances, to discover capabilities we didn’t know we possessed. But transformation terrifies us precisely because it means losing the familiar self.

Portal fantasy offers radical change with a crucial safety mechanism: the possibility of return. Even if return proves difficult or costly, its theoretical availability provides psychological comfort.

What’s more, portal narratives often present secondary worlds with clearer moral frameworks than our ambiguous reality.

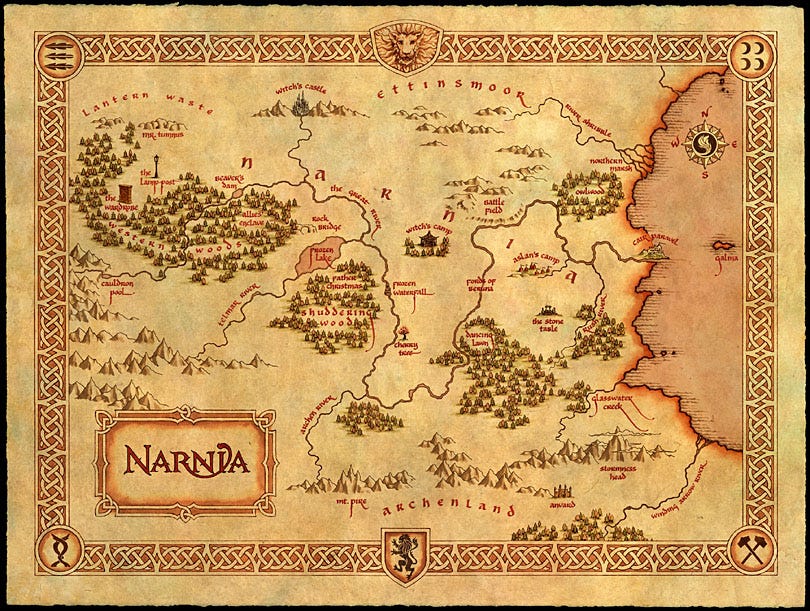

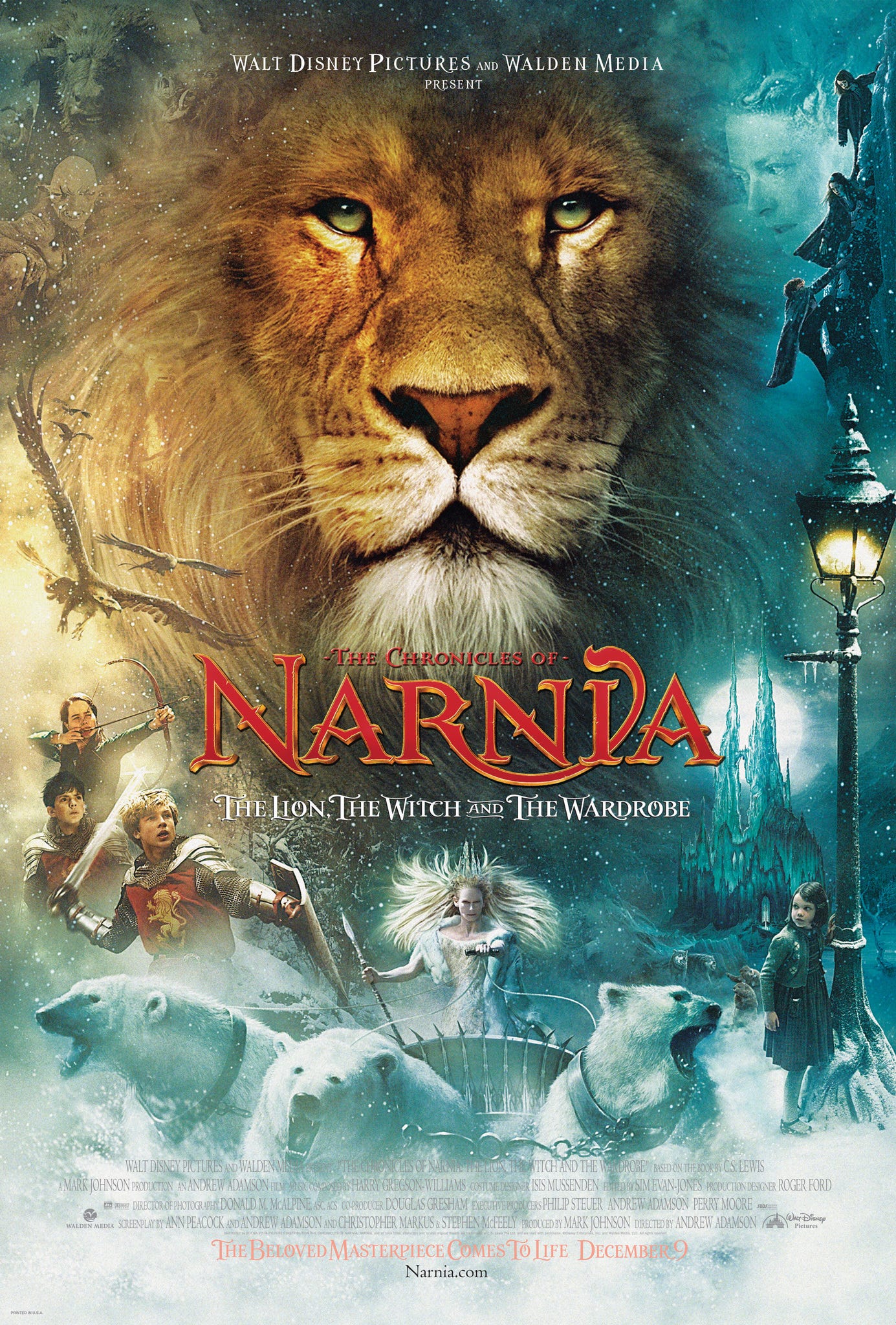

Narnia operates according to straightforward rules: Aslan represents good, the White Witch represents evil, loyalty and courage matter in demonstrable ways. This moral clarity appeals to minds struggling with contemporary ethical complexity. The portal crossing offers relief from relativism, even temporarily.

Finally, portals grant permission to act outside normal social constraints.

Characters forced through portals into strange worlds gain license to behave in ways their ordinary lives forbid.

Lucy Pevensie, a proper English schoolgirl, becomes a warrior queen. Alice, constrained by Victorian propriety, argues with royalty and challenges adult authority.

The portal crossing temporarily suspends social rules that govern identity, allowing characters to discover capabilities their normal contexts suppress.

But portal narratives function as more than escapist wish-fulfillment. They represent something deeper about consciousness itself. The threshold between worlds mirrors the threshold between different modes of perception.

We don’t necessarily travel to other realms; we learn to perceive differently, to recognize dimensions of reality our habitual consciousness filters out.

The mystic traditions across cultures describe enlightenment as a shift in perception rather than a change in external circumstances. The world remains the same; the perceiver transforms.

Portal fantasy dramatizes this epistemological threshold.

The character who crosses into the secondary world gains access to aspects of reality that exist always but remain invisible to those who haven’t crossed. They develop what James Joyce called “epiphanic” vision—the capacity to perceive the extraordinary within the ordinary.

This explains why portal stories emphasize that crossing is irrevocable in crucial ways.

Once you’ve seen through the threshold, you can’t unsee what lies beyond. Your consciousness expands to contain dual awareness—you know both worlds exist, both modes of perception operate.

This expansion can’t reverse. You might return physically to your original location, but you cannot return to your original state of consciousness.

Gil Eanes couldn’t “unsee” what lay beyond Cape Bojador. Once he knew the medieval cosmology was wrong, that knowledge became permanent.

He carried then a dual consciousness: he remembered believing in the boiling seas and skin-blackening sun, and he knew the truth of ordinary ocean continuing beyond arbitrary boundaries.

This doubled awareness changed not just his navigation but his entire relationship to received wisdom and authority.

Alice can’t return to seeing the world exactly as she did before falling down the rabbit hole. Even if Wonderland exists only in dream, the dream revealed aspects of reality—the arbitrary nature of social rules, the flexibility of logic, the constructedness of authority—that can’t be forgotten.

The portal crossing is epistemological as much as physical.

‘Going Home’: Why Coming Back Is Hardest

Portal fantasy protagonists consistently struggle with return to the “normal” world. This pattern appears so frequently across cultures and eras that it demands explanation beyond narrative convention.

Lucy Pevensie’s desperation to return to Narnia drives much of C.S. Lewis’s series. After experiencing significance, purpose, and magic in the secondary world, English boarding school feels insufficient, even unbearable.

Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver, having traveled through multiple strange lands, finds himself unable to reintegrate into English society. He ends his days in the stable, preferring the company of horses to humans because his perception has permanently shifted.

Chihiro in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away leaves the spirit world transformed, carrying knowledge and capability her previous self lacked. J.M. Barrie’s Wendy discovers she’s aging out of access to Neverland, a loss that feels more like death than natural development.

This narrative pattern reflects authentic psychological experience of transformative events.

Soldiers returning from war describe the impossibility of explaining combat to those who haven’t experienced it, the sense that civilian concerns feel trivial against what they’ve witnessed.

Travelers coming home from life-changing journeys often struggle to re-engage with daily routines that once provided satisfaction.

People emerging from profound grief or serious illness discover that others cannot comprehend the territory they’ve crossed through.

Anyone who has undergone genuine transformation recognizes the difficulty of returning to contexts that expect you to remain unchanged and behave ‘normally’.

The struggle isn’t primarily because home has changed, though it may have. The difficulty lies in the protagonist’s transformation.

The “real” world feels less real now, more arbitrary, more constructed. Its rules, which once seemed natural and necessary, now appear contingent and sometimes absurd. The knowledge gained from the other side makes ordinary life feel insufficient.

Maritime examples illuminate this pattern with particular clarity.

Sailors who crossed Cape Bojador couldn’t return to believing in medieval cosmology. They carried knowledge that contradicted cultural consensus, making them uncomfortable in their own communities.

Odysseus’s men who ate lotus fruit on the island of the Lotus-Eaters couldn’t return to their former desires and ambitions; the fruit revealed an alternative mode of existence that made their previous goals seem meaningless.

The Ancient Mariner in Coleridge’s poem is condemned to wander, compulsively telling his tale, because he cannot return to ordinary life after crossing the threshold into cursed waters where the dead crew worked the ship.

Celtic selkie tales capture this dynamic perfectly.

The selkie trapped on land by a stolen skin continues to exist, marries, bears children, engages in human life—but never stops hearing the sea’s call.

She functions in the terrestrial world while carrying constant awareness of the marine realm she’s been barred from accessing. Her divided consciousness—belonging fully to neither land nor sea, carrying knowledge of both—creates permanent restlessness.

When she finally recovers her skin and returns to the ocean, she cannot bring her human family with her. The portal crossing in either direction involves irrevocable loss.

Consciousness expands but cannot contract.

Once you’ve experienced expanded awareness, you cannot voluntarily reduce yourself to your previous limitations. The portal crossing grants enlarged perception, broader emotional range, deeper understanding. But consciousness at this expanded size no longer fits comfortably in contexts designed for its previous dimensions.

This is simultaneously gift and curse. The protagonist gains knowledge, capability, and perception unavailable to those who haven’t crossed. But they also lose the comfort of unexamined certainty, the peace of fitting seamlessly into their original community, the simplicity of life before dual consciousness.

Portal fantasy is honest about this exchange: transformation costs something. Growth means leaving parts of your former self behind.

Literary Architectures: How Authors Build Their Portals

Different authors construct portal crossings that emphasize distinct psychological dimensions of the threshold experience.

C.S. Lewis positions the wardrobe in The Chronicles of Narnia as a portal that appears to those who need it.

Lucy discovers Narnia during a rainy day game of hide-and-seek—she’s not searching for another world, which is precisely why she finds it. The wardrobe only works when approached without calculation or agenda.

This reflects how transformative experiences often arrive when we’re not forcing them, when we’ve relaxed our grip on controlling outcomes.

Lewis’s narrative arc makes return increasingly difficult. The Pevensie children can access Narnia multiple times in the early books, but each visit costs more. Eventually, they age out of access entirely.

Peter and Susan can no longer enter Narnia because they’ve become too focused on appearing mature, too invested in seeming adult.

The portal closes not because of arbitrary magic, but because a certain quality of consciousness—openness, wonder, willingness to believe—has calcified in them. How certain modes of perception become inaccessible as we age and accumulate social conditioning.

Lewis Carroll’s rabbit hole in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland operates differently. Alice doesn’t choose to fall; she tumbles down the tunnel in pursuit of the White Rabbit, landing in a realm where normal logic fails entirely.

The portal crossing in this instance involves loss of control—a fall rather than a step through a doorway.

Once in Wonderland, Alice discovers that the rules governing her ordinary existence no longer apply. Social hierarchies invert, size becomes fluid, time refuses to behave, language means whatever the speaker insists it means.

Carroll’s portal addresses the dream state where unconscious material surfaces, where the rational mind’s control dissolves.

Alice’s return involves “waking up”—but the narrative deliberately leaves ambiguous whether Wonderland was real or dream. This ambiguity matters, as some portals exist primarily in consciousness.

The boundary Carroll describes isn’t between physical locations but between modes of awareness, and the crossing is no less real for being internal.

Philip Pullman’s subtle knife in His Dark Materials allows characters to cut windows between parallel worlds. This weapon-tool transforms portal crossing from a passive experience into an active—almost violent, choice.

Characters can create ‘doors’ at will, control access, even weaponize the ability to cross between worlds. But Pullman’s narrative arc focuses on the consequences: too many portals weaken the fabric between worlds, allowing dangerous entities to pass through. The ultimate ethical choice requires closing all portals permanently, accepting that separation between worlds serves a necessary function.

Pullman’s portal architecture explores maturity as accepting limitation. The young protagonists initially see unlimited portal access as unqualified good—why shouldn’t worlds connect freely? But they learn that boundaries serve purposes, that infinite possibility can become destabilizing, that choosing one world means accepting what other worlds offer but you cannot access.

The final act of sealing the portals represents committing to one reality, one life, over the potential of infinite options, depth over breadth, focused engagement over scattered connection.

Ursula K. Le Guin uses the threshold between life and death as the ultimate portal in A Wizard of Earthsea and The Farthest Shore.

The wall separating the living from the dead can be crossed, but doing so costs dearly. Some of her most profound passages explore the temptation to abolish this boundary entirely—to end death, end change, end time. Her wizard protagonist must defend the threshold’s integrity, arguing that boundaries between states of being aren’t prison walls but necessary structures.

Le Guin’s portal philosophy again suggests how accepting limits can represent wisdom, rather than defeat.

The threshold between life and death, like the threshold between childhood and adulthood or innocence and experience, shouldn’t be crossed lightly. Some portals mark territories that require particular readiness, particular strength, particular willingness to accept consequences.

The desire to eliminate all crossings, to make all realms accessible at all times, reflects immaturity rather than enlightenment.

Contemporary portal fantasy continues exploring these themes with increasing sophistication.

Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away uses the portal crossing to dramatize coming of age. Chihiro enters the spirit world when her parents transform into pigs, forcing her to work in a bathhouse for spirits and gods.

The threshold crossing requires her to develop capabilities she didn’t know she possessed—courage, work ethic, loyalty, the ability to see through deception. She returns to the human world transformed, carrying new strength.

V.E. Schwab’s Shades of Magic series presents multiple parallel Londons—Grey London (our world), Red London (magic flourishes), White London (magic is dying), Black London (destroyed by magic).

Portals between these worlds once flowed freely, but are now tightly regulated after Black London’s catastrophic collapse. Schwab examines what happens when portal crossing becomes common, normalized, even commercialized. The rare individuals who can still cross between worlds wield tremendous power, but also bear heavy responsibility.

The Maritime Portal: Water as Threshold

Water’s properties make it ideal for portal narratives. Unlike solid land with fixed geography, water constantly shifts, creating and dissolving boundaries. The shore itself embodies permanent liminality—neither fully land nor fully sea, existing in perpetual flux as tides advance and retreat.

The horizon line over water creates a visual threshold more profound than any land horizon. On land, distance obscures detail but you understand that mountains, forests, and plains continue beyond sight.

The ocean horizon suggests something more absolute—the edge where vision fails, where the familiar world gives way to unknown depths and distances. Medieval cartographers placed “Here Be Dragons” in ocean territories precisely because water permitted imagining radically different realms.

Fog transforms familiar waters into alien territory within moments. A harbor you’ve navigated for years becomes strange when fog reduces visibility to meters. Landmarks disappear, distance becomes uncertain, direction grows ambiguous. Fog doesn’t transport you to another world; it reveals that the world you thought you knew contains aspects you haven’t perceived.

This makes fog perfect for portal narratives—it doesn’t require accepting magic or supernatural intervention, only recognizing that perception can shift radically.

Storms suspend normal rules entirely. Even experienced sailors become passengers during severe weather, at the mercy of forces beyond human control. Ships travel to places their crews never intended, arriving at islands that don’t appear on charts, in waters where normal navigation fails.

Storm-driven portal crossings feel psychologically authentic because storms genuinely do create threshold experiences—moments when ordinary competence fails and survival depends on factors beyond expertise.

The voyage structure allows for gradual transformation rather than instantaneous crossing. Where a wardrobe or mirror creates sharp before/after distinction, sea journeys permit incremental change.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner demonstrates the maritime portal’s psychological power. The mariner’s ship sails into Antarctic waters—territory beyond medieval European exploration, functionally “beyond the world.” Killing the albatross violates a sacred boundary, transforming natural voyage into cursed odyssey.

The mariner crosses into territory where the dead crew works the ship, where supernatural entities play dice for souls, where normal causality breaks down.

His crime isn’t simply killing a bird; it’s violating the threshold’s sanctity.

The albatross represented the boundary between normal and sacred, killing it collapsed the distinction between realms that should remain separate.

The curse condemns the mariner to perpetual wandering, compulsively telling his tale because he cannot return to ordinary life after crossing into cursed waters.

Modern maritime portal narratives continue this tradition. Yann Martel’s Life of Pi uses the Pacific Ocean as threshold space between competing narratives—the allegorical tale with the tiger, and the brutal human story Pi refuses to tell directly.

The ocean voyage becomes portal between reality and the story that makes reality bearable. Pi crosses repeatedly between versions, finally asking which story his listeners prefer to believe.

Ponyo presents the flood as portal crossing, the rising water temporarily collapsing boundaries between human and spirit worlds, allowing the fish-girl Ponyo to become human and the boy Sosuke to enter the ocean realm.

The passage exists only during the flood’s duration—a temporary portal that will close once water recedes. This captures the fleeting nature of certain threshold experiences: windows that open briefly, require immediate decision, then close permanently.

Disney’s Moana uses crossing the reef as primary portal moment. The reef marks the boundary of the known world for Moana’s people, who have stopped voyaging beyond it.

Crossing through the reef gap requires overcoming not just nautical challenges but psychological barriers—generations of inherited fear, cultural prohibitions, and internalized limitations.

Moana’s return, bearing knowledge from beyond the reef, transforms her entire culture. She becomes living proof that the portal can be crossed, that the ancestors’ voyaging tradition can be recovered.

Craft Implications: Building Believable Portal Crossings

Writers constructing portal narratives face specific challenges in making threshold crossings feel psychologically authentic rather than arbitrary.

First of all, portals require clear, consistent rules.

Not every rule must be explained immediately, but the portal’s operation shouldn’t shift to serve plot convenience.

C.S. Lewis establishes that the wardrobe only functions when characters aren’t trying to use it instrumentally—Lucy finds Narnia during innocent play, but when she tries to show her siblings, the portal refuses to open. This rule creates narrative tension while maintaining internal logic.

Philip Pullman’s subtle knife cuts windows between worlds, but each cut weakens the fabric separating realities. Use too many portals and dangerous entities slip through. This limitation creates meaningful choices: characters must weigh the benefit of opening a portal against the cost of weakening boundaries. The rules serve story while maintaining consistency.

Portals lacking clear rules feel arbitrary. If the wardrobe works whenever the plot requires it, tension evaporates. If characters can cut windows anywhere without consequence, stakes collapse. Rules create resistance, and resistance generates meaningful narrative.

Second, crossing must change the protagonist irrevocably.

Portal fantasy fails when characters pass between worlds but remain essentially unchanged. The threshold crossing should mark genuine transformation—new capabilities developed, old certainties dissolved, perception fundamentally altered.

Chihiro in Spirited Away enters the spirit world as frightened child clinging to her parents. Working in the bathhouse, she develops courage, resourcefulness, and loyalty. She learns to see through deception, advocate for herself, make ethical choices under pressure. Returning to the human world, she’s visibly different—standing taller, moving with confidence, prepared for challenges ahead. The portal crossing transformed her.

Alice returns from Wonderland changed in subtle but significant ways. She’s learned to question authority, recognize the arbitrariness of social rules, defend her own perception against social pressure. The change isn’t dramatic—she’s still a child—but the experience has shifted something fundamental in how she relates to the world.

Third, both worlds must feel real and substantial.

The “normal” world can’t function as mere launchpad for getting to the interesting secondary world. If ordinary reality feels thin, artificial, or dismissible, the portal crossing loses significance.

Philip Pullman’s Oxford in His Dark Materials receives as much careful attention as the parallel worlds. We understand Lyra’s life in Jordan College, the political tensions in her world, the theological framework governing society.

When she crosses into our London, both locations carry equal weight. The tension between worlds creates meaning precisely because both matter.

C.S. Lewis makes the Pevensie children’s life in wartime England feel real—the anxiety of living with a distant relative, the boredom of rainy days, the sibling dynamics. This grounds the fantasy, making Narnia’s wonder register more powerfully because we know what the children are leaving behind.

Fourth, return must cost something.

Coming home after threshold crossing should be difficult. The protagonist has gained expanded consciousness, new capabilities, knowledge unavailable to those who haven’t crossed. But this expansion creates problems.

How do you explain to people who haven’t crossed what you’ve experienced? How do you function in ordinary contexts when you’ve seen extraordinary possibilities?

Lewis’s later Narnia books acknowledge this difficulty. Peter and Susan, having been kings and queens in Narnia, struggle to return to being schoolchildren in England. Susan eventually copes by convincing herself Narnia was childish imagination. Peter’s faith in Narnia creates social difficulties—how do you maintain belief in a world others consider fantasy?

Writers should ask: What does my protagonist lose by crossing? What do they gain? How does expanded consciousness create problems when they return to contexts that expect them unchanged? If return costs nothing, the portal crossing probably wasn’t deep enough.

Common portal mistakes include arbitrary access (the portal works whenever plot requires it), absence of meaningful change (characters return essentially unchanged), inconsistent rules (the portal operates differently each time), easy return (no cost to coming back), and thin worlds (the secondary world lacks depth and internal logic).

The Door That Won’t Close

Gil Eanes returned from his voyage beyond Cape Bojador to report that the waters didn’t boil, the sun burned no hotter, no monsters lurked in the depths. His discovery might seem like proving there was no portal after all—just ordinary ocean continuing past an arbitrary point. But in crucial ways, Bojador was a portal. Not to a different physical world, but to different consciousness.

The medieval sailors who turned back from Bojador weren’t cowards—they were acting on the best information available to them. Generations of inherited wisdom, cultural consensus, and religious authority all confirmed that passage beyond the cape led to catastrophe.

Crossing that threshold required more than nautical skill. It required willingness to test inherited knowledge against direct experience, to privilege observation over authority, to accept that collective belief might be wrong.

Once Eanes crossed and returned, that knowledge couldn’t be contained. Medieval cosmology didn’t collapse immediately—cultural change rarely happens instantaneously—but the portal had been breached.

Consciousness that had accepted limits as absolute discovered those limits were constructed, arbitrary, crossable.

The Age of Exploration began, not because the physical world changed, but because human perception crossed a line it couldn’t recross.

We return to portal narratives generation after generation because we recognize their fundamental truth. We all cross thresholds that change us irrevocably. We all long for worlds where clearer rules apply, where courage matters in demonstrable ways, where transformation is possible.

We all struggle to return “home” after profound change, carrying knowledge that makes us aliens in familiar territory.

We all contain dual consciousness—remembering both who we were and who we’ve become.

Portal fantasy suggests transformation is possible. Different worlds exist, accessible if we’re brave enough to cross. We’re not trapped in single modes of being. The door might open when we need it most—not because magic intervenes, but because thresholds exist always, waiting for readiness.

But portal fantasy also warns: not all crossings should be made. Some thresholds change you more than you’re ready for. You can’t always return.

Choose your crossings carefully, because once you’ve seen through the threshold, you can’t unsee what lies beyond.

A fog bank rolls in off the coast, obscuring the familiar shoreline. A sailor stands at the helm, watching the world transform within minutes.

The threshold exists always, waiting.

The question then isn’t whether portals are real, but rather are we ready to cross the one life presents us with, knowing we cannot return unchanged?

Author Note: If you managed it through, I commend you. This was a beast to get through, but I hope you enjoyed reading it at least half as much as I did writing it for you.

Leave your mark in the comments with a 🏆 or a #EndNoteSquad (or both) if so.

GO DEEPER:

What thresholds have you crossed that changed you irrevocably? And what part of you still stands at the portal, wondering if you can return to who you were before?

These prompts are meant for self-reflection and journaling, but I invite you to share your thoughts in the comments.

Previous in this series: “Isolation in Literature: When Solitude Breaks the Mind” – examining what prolonged isolation does to human consciousness and how literature has documented these effects with remarkable accuracy.

Next in this series: “Writing Meaningful Cost: What the Odyssey Teaches About True Stakes in Fiction” – exploring how to create characters who truly pay for their goals and what classical literature teaches about authentic consequences.

About the Author:

Morgan A. Drake crafts dark maritime fantasy that explores the boundaries between historical seafaring traditions and the supernatural. Drawing on years of research into maritime mysteries and folklore, Morgan creates worlds where the line between natural and otherworldly perils blurs with the horizon.

You can find Morgan's fiction at:

References and Further Reading

Primary Texts (Literature & Mythology)

Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. 1865.

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. 1798.

Gaiman, Neil. Coraline. HarperCollins, 2002.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles, Penguin, 1996.

Le Guin, Ursula K. A Wizard of Earthsea. Parnassus, 1968.

—. The Farthest Shore. Atheneum, 1972.

Lewis, C. S. The Chronicles of Narnia. 1950–56.

Martel, Yann. Life of Pi. Knopf, 2001.

Miyazaki, Hayao. Spirited Away. Studio Ghibli, 2001.

Pullman, Philip. His Dark Materials trilogy. Scholastic, 1995–2000.

Schwab, V.E. Shades of Magic trilogy. Tor Books, 2015–17.

Swift, Jonathan. Gulliver’s Travels. 1726.

Yann Martel, Life of Pi. Knopf, 2001.

Historical Accounts & Maritime Exploration

Boia, Lucian. Great Explorations: The World’s First Explorers. University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Diffie, Bailey, and George Winius. Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press, 1977.

Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe. Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. Norton, 2006.

Henige, David. “Gil Eanes and the Discovery of Cape Bojador.” Journal of African History, vol. 13, no. 1, 1972.

Padrão, Luís Filipe Thomaz. The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415–1825. Carcanet Press, 1994.

Folklore, Mythology & Cultural Transmission

Briggs, Katherine. An Encyclopedia of Fairies. Pantheon Books, 1976.

MacCana, Proinsias. Celtic Mythology. Hamlyn, 1970.

Mayor, Adrienne. The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women Across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press, 2014.

O’Rahilly, Thomas F. Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1946.

Seki, Keigo. Folktales of Japan. University of Chicago Press, 1966.

Thompson, Stith. Motif-Index of Folk Literature. Indiana University Press, 1955–58.

Narrative Theory, Story Structure & Fantasy Studies

Attebery, Brian. Strategies of Fantasy. University of Indiana Press, 1992.

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. Knopf, 1976.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press, 1949.

Clute, John, and John Grant, editors. The Encyclopedia of Fantasy. St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

Mendlesohn, Farah. Rhetorics of Fantasy. Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Fantastic. Cornell University Press, 1975.

Warner, Marina. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1994.

Psychology, Liminality & Transformation

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, 1990.

Kegan, Robert. The Evolving Self. Harvard University Press, 1982.

Mezirow, Jack. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. Jossey-Bass, 1991.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Aldine Publishing, 1969.

Van Gennep, Arnold. The Rites of Passage. University of Chicago Press, 1960 (original 1909).

Yalom, Irvin D. Existential Psychotherapy. Basic Books, 1980.

Philosophy, Epistemology & Perception

Bachelard, Gaston. Water and Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Matter. Dallas Institute, 1983.

James, William. The Varieties of Religious Experience. Longmans, Green & Co., 1902.

Joyce, James. Stephen Hero. New Directions, 1944 — (for early writings on “epiphany”).

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge, 1962.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

Maritime Studies & the Psychology of the Sea

Corbin, Alain. The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside in the Western World. University of California Press, 1994.

De Souza, Philip. Seafaring and Civilization. Profile Books, 2001.

Puchala, Donald. The Psychology of the Sea: Liminality, Danger, and Imagination in Maritime Traditions. (If you prefer, I can swap this for more academic maritime psychology texts.)

Rediker, Marcus. Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

A note on the Images: Unless credited, illustrations accompanying the posts are creative interpretations designed to evoke the atmosphere of maritime legend rather than serve as historical documentation. For historical visual references, please consult the sources listed in the references section.

Again you have inspired me. I will have to work portals into a story or two now. Wonderful read.